How hand rogueing is winning the battle against blackgrass

Andrew’s 660-ha unit Glebe Farm, Leadenham, Lincolnshire, lies about 190km north of London and has soils ranging from light sand to heavy clay. On the heavier clays, herbicide-resistant blackgrass had become a severe problem in winter wheat and chemical control costs were mounting.

“It was clear herbicide alone was no longer tackling the problem and we needed to devise a more holistic strategy,” says Andrew. “We decided we had to eat, sleep and breathe blackgrass control. Now every decision we take is weighed up against what impact it will have on our blackgrass population. If it is negative for blackgrass control, then we don’t do it.”

He devised a comprehensive control strategy including - early cultivation, a switch to spring cropping, selecting disease-resistant varieties and chemical control. At the heart of the strategy is large-scale, organised hand rogueing with gangs of up to 10 workers, methodically tackling crops field-by-field. The timing of pulling up the blackgrass is crucial. If the teams go in too early there will be more blackgrass coming through by the time the crop is harvested and further rogueing will be needed, Andrew explains.

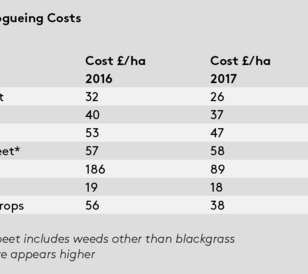

In one field last year the team carried out rogueing then had to return twice more to take out plants as they regrew, incurring a total cost of £186/ha. But if rogueing is left too late, the plant will produce seed.

“The aim is to never let the blackgrass seed – if this happens it will return to the soil and infest future crops. So, we have a narrow window, normally only about three weeks – blackgrass must be above crop height but once flowering is complete, seed starts to set and become viable, this is usually mid-June for winter cereals and end of June for spring cereals,” says Andrew. “If we catch it at this stage we can be sure of getting 98% of the plants. Our aim is to not see any blackgrass from the combine, which we have done for the last four years.”

Because the policy is integral to the strategy it is carefully costed, and results analyzsed. The gang records the total man hours spent rogueing in each field and writes the figure down on a farm map. At the end of the week the map is handed over and the figures analyzed using the farm’s Gatekeeper management software.

Using a labour figure of £10.20/hour/head the software calculates a cost for each field and divides it by the area to arrive at a cost per hectare. Falling blackgrass control costs show the policy is working, says Andrew.

“We are so religious about the process that we are not just seeing chemical control costs coming down but the rogueing costs are falling as well as we clear fields and prevent reseeding,” reports Andrew.

Further analysis of the figures reveals other useful data for management planning. Spring barley control costs have fallen more quickly than other spring-sown crops. Spring barley’s competitiveness against blackgrass is well known and these figures confirm that which is important information when devising rotations and maximizing yields.

“We have introduced a traffic light system to denote which fields are a concern for blackgrass,” Andrew says.

Red: is for the fields with the biggest burden on the heavy soils. Winter wheat is no longer planted in red zone fields because the blackgrass seed population is so high in the soil, switching to spring cropping is the only option for a number of years.

Amber: is where there is a manageable problem or fields which were ‘red’ fields but our policy is reducing it.

Green: is blackgrass free fields, predominantly on the lighter soils.

“We are already seeing a shift in the number of fields from red to amber as our efforts take effect, but I will not say we are seeing fields switch from amber to green because I think it will be many years before our soils contain no blackgrass seeds at all. We can see this through the analysis which shows the situation has improved for winter wheat crops through a reduction in the amount of time needed to rogue fields,” says Andrew.

Winter wheat rogueing costs have fallen from the highest average crop cost of £56/ha to the lowest at £26/ha. It confirms to Andrew that the rogueing is working in conjunction with a policy of switching from winter to spring-sown crops in the fields with the heaviest blackgrass populations. The extent of that switch is evident in the changing percentages of spring to winter crops. In 2013 just 4% of the rotation was spring-sown with winter wheat accounting for 45% of the cropping. This year winter wheat has taken up 19% of the area and the proportion of spring sown crops has grown to 41%.

The expected reduction in yield associated with spring crops has not been as great as Andrew had expected. “Spring wheat achieved 9.4t/ha so my average yield is surprisingly high. Any spend on the crop doesn’t usually start until the spring easing cash flow and inputs on spring crops are far lower. For example, we only needed two fungicide applications on the spring wheat,” Andrew says.

It shows a clean spring wheat or spring barley will produce better margins than a winter wheat with a heavy infestation of blackgrass, he adds.

Herbicide costs too have fallen and when they are added to the rogueing costs the overall figure shows the benefit of the integrated approach. In 2016 Glebe Farm’s total average weed control cost – including chemical control and hand rogueing - was £137/ha. That compares well with the previous herbicide-only approach of up to £216/ha.

“It is a good news story all round because we are better protecting the environment by reducing our reliance on herbicides. We are also reducing the likelihood of increasing resistance and so preserving chemical controls for future use,” Andrew says.

The first part of the jigsaw is early cultivation which creates the firm seedbed needed to allow early spring sowing. The norm on most farms is to carry out cultivations through the autumn but fieldwork at Glebe Farm, particularly on heavy soils, is completed months earlier in August as a disc, tine and press follow the combine. By the third week in August this year, cultivations were completed for about 80% of land allocated for spring sowing.

The aim is to create the biggest window possible between crops.

“In fields destined for winter wheat, cultivations are completed in July or early August. But drilling doesn’t take place until October allowing the autumn flush of blackgrass and other weeds to be taken out with glyphosate before the new crop is planted. And, because the soil is worked while it is still firm and dry, we avoid compaction damage which can occur once the wet weather has set in,” says Andrew. “Soil goes into the winter dry and in fantastic condition and comes out of the winter dry and still in fantastic condition.”

That means, in the spring, the farm has a head start because the land is drier allowing crops to be drilled sooner, maximizing yields and making the spring-sown option more viable.

Image Gallery

Related Articles

Partnership that Grows Together: ADAMA Romania’s Collaborative Edge

How the Cazado® Launch Embodies Value Innovation